The military tactics of ancient Greece remained the same for 300 years once it entered the Archaic Period, up to 480 BC. During this time there was mostly fighting among the city-states, who would all abide by similar rules for combat, resulting in the lack of a need to change their warfare. It was not till the end of this age, during the battles with Persia in 490 BC, that Greece really started changing tactics and armor. After defeating the Persian invasion, where the heavily armored army was key to their victory, the Greek people started to create lighter armor designs that could improve the mobility of their armies but still maintained good protection. Lighter weight of armors was achieved by reducing the thickness and making more space for vision and hearing to remove materials from the existing designs, and by using different materials such as using less metals and more strengthened linen or leather. Scale armor also appeared in Greece during this period, which combines the flexibility of the linen and the strength of metal. Some other changes to armors were also made to adjust to their new equipments or new opponents.

The hoplite, the common infantry unit of the time, was a heavily armored unit that was equipped with a bronze helmet, corslet, greaves, and large circular shield, called the hoplon, which weighed twelve to fifteen pounds alone. They were typically had a height of 5’2” to 5’4” and mainly wielded a spear with a backup sword called a xiphos, used if the spear had to be discarded. The gear all together, called the panoply, weighed a massive 50 to 60 pounds.

Interestingly, there is a great deal of variety among artifacts due to regionalism among the city-states. Each one had a unique culture and therefore different versions of the armor of the hoplites. Even naval battle did not see a change until the Peloponnesian Wars in 430-400 BC. The most drastic change in warfare was brought about during the following Classical Period, by Philip II’s noticeable introduction of siege tactics as a major tool and Alexander’s new tactics and changes to arms and armor.

Materials and Armor Smithing Techniques

In Greece during this time period, techniques in metalworking and materials from earlier times continued to be used and developed. However, some new materials were used to create armors that were mainly made of bronze. Linen and leather were introduced to make up major part of the body armors, especially the cuirass. This period also witnessed gold and silver being used more widely and for more purposes. For example, in Classical times, gold and silver vessels were made in southern Greece, although none of them have survived. Regions such as central Macedonia, or Alexandria in Hellenistic time, were places of exceptional silversmiths and luxurious products from silver and gold.

HELMETS |

|

|

Helmets were probably the most varied form of armor among the Greeks, due to the regionalism of different city-states and attempts to correct flaws with other helmets. They were usually constructed of bronze and possessed some sort of crest. The main feature of these helmets is the impressive work of the smith to beat out the entire helmet from one sheet of bronze. The helmet usually had a T shape for the eyes and mouth and often had a nose-guard. This innovation was so great that similar design types could be seen 2,000 years later in Italian armor. |

|

|

Name: Chalcidian helmet. Origin: Greece, late 6th to early 5th century BC. Materials: bronze. Compared to Corinthian helmet, this helmet exposes a majority of the face, and has more space for the eyes and the ears. It is also thinner than its earlier Corinthian counterpart. This helmet consists of just one piece of armor and should be made simply using hammering techniques. |

|

|

Name: Thracian helmet. Origin: Thrace, Greece, 5th century BC and throughout Hellenistic period. Material: bronze. This design was inspired by the everyday cap worn in Thrace. It has a rising at the top to a forward pointing peak. These types of high crowned helmets were used widely probably to defend against the slashing swords of the Celts. Another prominent feature is the combined forehead-guard and eye-shade. This helmet was greatly popular in the farther north of Greece in 5th BC. |

|

ARMORS |

|

|

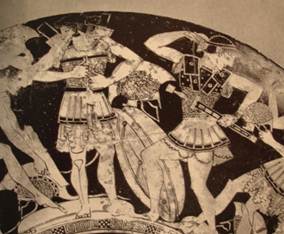

The armor consisted of two large shoulder-pieces, called epomides, that were attached at the back and fastened over to the chest. It is hard to tell what parts of the body of the armor was metal or leather. It was most likely leather with bronze plates attached and metal scales down the sides. Some variations have the metal scale armor along the front as well. Towards the bottom of the corslet was a skirt like area formed by leather flaps called pteruges. Another variation, not used as much, developed around this time was similar to the original plate corslet, but was carefully shaped to fit the wearer and was decorated with the main muscles in the torso. This type of armor is seen worn by Alexander’s Macedonian cavalry. |

|

Snodgrass, Arms and armors of the Greeks. |

Name: Linen cuirass illustrated on a vase. Origin: ancient Greece in Classical period (6th to 4th BC) Material: linen, sometimes with metal. The portrayals depicted two large shoulder pieces, permanently attached at the back, brought over the shoulders, and fastened by laces to the chest. The corselet extended well below the waist, with a sort of skirt formed of one or two rows of leather flaps. This type of cuirass provides excellent flexibility and ventilation. |

Connolly, P. (1998), Greece and Rome at War. |

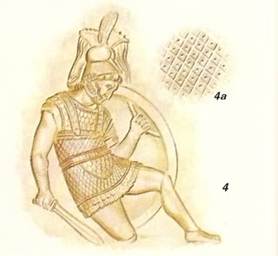

Name: quilted linen cuirass Origin: Greece, through Classical and Hellenistic period. Materials: linen, strengthened with thick leather and metal. Linen can be quilted to provide better strength, and each square in the figure 4a can be armed with a riveted nail head. Quilted cuirass was usually worn with scales armor, consisting of many metal scale attached together, covering the chest or stomach to improve protection and keep a good mobility. |

WEAPONS |

|

|

The primary weapon of the hoplite was the thrusting spear. In the event that the spear was broken or lost, the hoplite had to quickly switch to a small sword called the xiphos. This weapon persisted through much of the sixth century, but eventually was overshadowed by the kopis. This was a short, single-edged sword with a slight curve. The back of the sword and the cutting edge were both convex, giving the sword an appropriate weight towards the tip. The hilt had a hand-guard and curved around the hand. It was specifically designed as a cutting weapon that would be drawn back behind the left shoulder and swung downwards. |

|

SHIELDS |

|

|

The shield or hoplon protected the hoplite from his chin down too his knee, having a usual diameter of three feet. The shield was round and slightly concave in shape except for the rim. The hoplon was made from wood and reinforced with bronze. The rim was faced with bronze and sometimes the entire shield was also faced in bronze. Similar round shields have existed for a while and across other cultures. On the inside of the shield was a bronze strip that bowed outward called the porpax, which the hoplite’s arm would go through up to the elbow. The hand of this arm could then grip a leather handle called the antilabe. |

|

WAR FLEETS |

|

|

The main ship used was called the trireme, not much is known about it except that it was stouter and harder to maneuver than the Persian ships and possessed a bronze point on the bow. Athens turned into a naval superpower at the start of the Peloponnesian War, making their navy their strong point to Sparta’s land forces. Athens developed complex and demanding tactics that only people of their skill could perform. Some tactics included rowing straight at the enemy, only to veer off at the last second to destroy the enemy ships oars. They could also quickly maneuver behind the other ship or to its side to ram and tip it. |

|

Integrative Materials Design Center - Worcester Polytechnic Institute